I’m currently reading John Carey’s What Good Are The Arts?, a book designed to provoke all art-lovers into a steaming maelstrom of outrage. Carey’s intention is to debunk all the good old myths about art making you feel spiritually uplifted, or turning you into a better person, or actually having much valid purpose at all. You have to bear in mind that this man is a very distinguished literary scholar from Oxford, and these kind of positions can send you either way. At heart, Carey’s aim is an honourable one: he wants to trounce all those pretentious art critics who pour scorn on the ‘lesser’ forms of art, or who have self-aggrandizing intentions attached to their aesthetic appreciation. However, Carey’s method for doing this is to pour scorn on just about any artistic theory, practice or perspective that he can lay his hands on. Attacking other people’s arguments is always, for me, the lowest form of criticism. Believe me, it’s always possible, and pretty easy to do once you’ve got your eye in. I like to see critics constructing positions and creating thought out of their investigations, but that’s a personal thing. In Carey’s favour, he’s very funny, very astute, incredibly well-read, and a real master of elegant English.

So let’s have a look at a classic Carey moment, when he’s tackling one of the oldest arguments surrounding art, and that’s whether or not we can honestly, and usefully, mark a clear distinction between the class-laden categories of high art and low art. You’ll perhaps not be surprised to know that Carey’s take on this is that we can’t, and his argument pokes fun at all the frankly ridiculous claims people have made across the ages for the value and the importance of ‘high’ art. Here he is at play, getting his teeth into the unfortunate critic, John Tusa, who has foolishly proposed a belief in ‘absolute quality’ in the high arts which he equates with their ‘difficulty’:

‘”The fact is,” Tusa explains, “that opera is not like dipping into a box of chocolates. It is demanding, difficult.” Despite this assurance, the association of opera with difficulty seems questionable. What sort of difficulty, it might be asked, do those attending opera encounter? What is difficult about sitting on plush seats and listening to music and singing? Getting served at the bar in the interval often requires some effort, it is true, but even that could hardly qualify as difficult compared with most people’s day work. The well-fed, well-swaddled beneficiaries of corporate entertainment leaving Covent Garden after a performance and hailing their chauffeurs do not look as if they have been subjected to arduous exercise, mental or physical…. The colossal injections of other people’s money needed to maintain [The Royal Opera House] are notorious. In 1996 alone it swallowed £78 million of lottery funding… As Tusa says, opera is not like dipping into a box of chocolates. It is very much more expensive.’

Ok, so we can see where Carey’s going with this, even though he doesn’t state it directly. The argument about difficulty is in fact never really addressed, in favour of attacking opera for the remnants of the old class system that still cling to it, and for its drain on public resources. Television and film, for instance, swallow up more than that amount of money in the UK, but they (more or less) have the grace to support themselves commercially. Carey does go on to talk about ‘difficulty’ taking the crossword puzzle as his preferred example of a practice that would warrant the adjective, but this is equally handled with the same dismissive air. What high art calls ‘difficult’ is what most sane people would call ‘unintelligible’ Carey claims. So whilst I admire Carey for his bite and verve, I think he undermines his own arguments by the sheer vitriol he injects into them.

Carey will ultimately dismiss the distinction between high and low art as impossible to maintain, but I think we can do something better than that with it. First of all we have to stop seeing the categories of high and low as being mutually exclusive. Quite a lot of operas, for instance, will include elements of farce, or romance, or pantomime, just as a television cartoon ostensibly for children, like The Simpsons, is a fantastic example of relentlessly subversive, parodic, allusive elements disguised under a sugary outer coating. So it’s incredibly rare, in my opinion, to come across a pure example of ‘high’ or ‘low’ art. What we get is far more complex and mixed up than that. The way I would distinguish between those high and low elements, is to see ‘low’ or commercial or mass media art as being formulated in order to satisfy the desires and expectations of its audience. Take Mills and Boon/Harlequin romance books, for instance. Every one published is subject to a rigourous assessment by a team of readers who will fill in a detailed questionnaire as to the plot, characters, conclusion, sexual content and so on, of the story, and say whether or not it corresponded to what they liked to read in a book. The data from these assessments is then turned into strict guidelines for the in-house authors, who must follow them to the letter. The whole point of these books is that they comfort and reassure readers by providing them with exactly what they want. By comparison, we might define those ‘high’ elements of art as the ones that challenge or question our expectations, whether they be about the world we live in, or the way that an artwork ‘ought’ to be put together. Well, I don’t know what you think, but this kind of works for me.

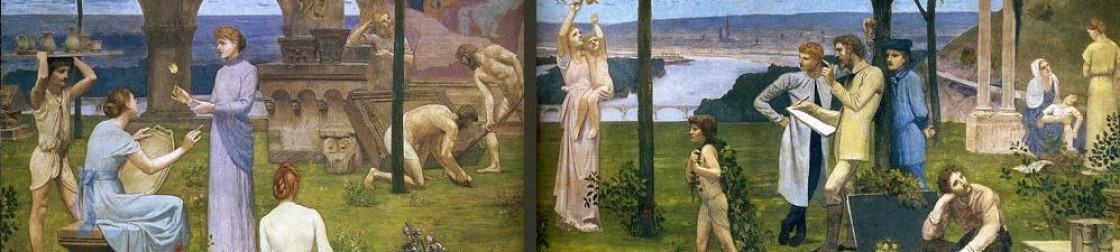

There’s another point I’d like to make, though, about this so-called battle between high and low art. To hear Carey talk, you’d think that the world was split into a toffee-nosed elite of high art lovers who spent their days venting their spleen and pouring their disdain onto the gentle masses, who ask for nothing more than to humbly enjoy the crumbs of art thrown down to them. This kind of judgement of art – the kind designed to make the judge feel superior over others – is by no means confined to the world of supposed ‘high’ art connoisseurs. I am quite convinced that no opera buff would ever be as rude to a Barry Manilow fan as, say, a fervent supporter of The Prodigy. Soap opera fans across the world might hail Dallas as a king amongst television dramas whilst dismissing Dynasty as pointless tripe. What I’m trying to say is that there is no one who doesn’t prefer one type of art to another, or dislike one form more than another, without attaching some form of value judgement to that preference. And what’s more, attaching value to art, privileging one kind over another, celebrating the qualities of pop or Pre-Raphaelite painting, or arthouse cinema or crime fiction because those genres or schools are simply better than others, is one of the great pleasures bound up in enjoying and responding to art. Ok, it shouldn’t be used as a tool of subjugation, but come on, let’s face it, we’re talking about art here. Liking Barry Manilow was never the reason anyone was sent to the gas chambers. But what we do need to acknowledge, is that intellect will never govern artistic appreciation because (as I think Carey’s own arguments clearly show), our response to it is every bit as much about emotion, as it is about reason.

“Liking Barry Manilow was never the reason anyone was sent to the gas chambers.” But perhaps it should be. But seriously, you make some very interesting points, and I think that your assessment that some types of art appreciation enables one to feel superior to another is spot on. The high/low debates appear to be based on the supposition that one’s aesthetics are either better informed than those of the unwashed masses or are more real and authentic than those of the “toffee-nosed” (I love that phrase) elite. I agree with you that it’s about emotion as much as anything else; I would bet that Carey’s problem with this line of thinking is that emtional responses are not easy for someone like him to quantify and analyze. I also think that the inability to quantify and analyze is one of the powers of art.

As husbands and boyfriends can all attest, there are too classes of “other women” that correspond closely to the categories of high and low art.

Women that my wife must admit are irresistibly attractive have mostly achieved a certain age and owe at least a good bit of their allure to their wit and intelligence and the apparent depth of their emotions and characters. On the other hand, women that my wife is appalled to discover I have a yearning to couple with we will categorize as low art.

I am no less attracted to one than to the other. And I readily admit to my need to indulge my fantasy life with aspirations toward both types. Still, there may well be value in trying to tease out the qualities that make them different. But I will not tolerate anyone trying to draw those distinctions for me.

Bikeprof – that is such an uncannily insightful point. Carey talks a great deal in this chapter about the way we cannot make claims for what art does unless we are prepared to conduct wide-ranging market research. I’m so impressed that you should be able to see that would be his come-back. But I’m firmly with you – being unquantifable is a very big tick in art’s favour for me. We have to think about it and assess it without falling back on statistics. David – your distinctions did make me laugh. My husband has called me ‘high maintenance’ before now, but I’m not sure whether that’s the same thing… Still, you’re quite right that beauty in all its forms and manifestations is very much in the eye of the beholder, no matter what theories we construct!

“attaching value to art, privileging one kind over another, celebrating the qualities of pop or Pre-Raphaelite painting, or arthouse cinema or crime fiction because those genres or schools are simply better than others, is one of the great pleasures bound up in enjoying and responding to art”

AMEN!!! 😉

You wrote in a comment above: beauty in all its forms and manifestations is very much in the eye of the beholder. But is “beauty” the same thing as “art”? I think that there have been many works of art created that are far from beautiful — nor are they meant to be. I think that is often a stumbling point for those who disdain “modern” art (when they really mean “contemporary”, but that’s another post….). In other words, there can be an expectation that a thing of beauty, rather than something that is meant to provoke, is inherent in some people’s definition of art. In a way, I think that is similar to what those who self-righteously critize popular culture for not being art (e.g., the popular tv drama, the Harlequin romance) believe: it doesn’t meet a specific definition and therefore is less valid, merely a pretender. There may be other reasons that a particular piece should be considered as art, but we stop at the concrete definition.

Isn’t art suppose to be jarring? Meant to be a perspective on how the artist — and the person reacting to the artist’s work — sees the world? That might not always be beautiful, either at the time of creation or by later standards, but it is no less valid. On the other hand, if art is only meant to reflect ‘beauty’, then why don’t we just paint pretty pictures of flowers…..if one can do so without injecting his/her worldview.

All of this is to say that I agree with you Litlove: it is an emotional response, not a quantifiable one. Art is in the eye of the beholder — and the beholder’s non-rational mind. To think otherwise is to suggest that one deprive others of something at the heart of human experience by denegrating their reactions and experiences to being less than worthwhile. For the opera aficiando to condemn the rapper (or fill in the blank with your personal example), is no better than a romance reader to deride a prize-winning author for being stuffy and inaccessible and, by extension, condemn all works of fiction that do not fall into her favorite genre.

I haven’t read Carey’s book yet, although it is sitting on the shelf. I did read a review that indicated that he only holds literature (only certain types, I suspect) as worthwhile for uplifting one’s being, something I find humorously self-serving as Carey is a literary critic.

Pingback: Pure examples of ‘high’ or ‘low’ art « Jahsonic

Frank Zappa, as unlike Barry Manilow as you can find, once wrote “Art needs to be in a frame. That way we know when the Art stops and the wall begins”. For art is a reflection of our world. Not always a comfortable reflection because it can, along with the beauty in our lives, show those dark, nasty secrets which we all possess and hope that no one else ever notices. Hieronymus Bosch (Garden of Earthly Delights) reflects our fears as honestly as Rubens does our secret desires and Van Gogh our eye for beauty. Literature in the form of novels is a latecomer to the arts world with the first novel only being written some four hundred years ago and perhaps this explains why it is such a pushy child. Poetry and performance have been around since the beginning of time, along with music and painting so these are the targets of a jealous literatii. Oops, this is a literature group, isn’t it! 🙂

I don’t know who wrote it but here is a thought for all Booker hopefuls “The key to winning Booker prizes is to know this: the judging committee simply weighs the book, then divides the weight in ounces by the average number of adjectives per noun. If the resulting integer is positive, the book is dropped from contention.”

And Calvin, speaking to Hobbes, described a wonderful discovery, “The purpose of writing is to inflate weak ideas, obscure pure reasoning, and inhibit clarity.

With a little pratice, writing can be an intimidating and impenetrable fog!”

Nice post — I like your point about emotion in our judgments of art, and I like your point and Bikeprof’s that an emphasis on emotional response can make certain kinds of critics nervous and uncomfortable. I also appreciate your commitment to offering a positive alternative to Carey’s not-very-convincing approach.

And one more thing — I suppose part of the fun of talking about literature can come from figuring out which works of art fit the two categories you describe — fulfilling expectations or challenging them. How often would people disagree on how to categorize specific examples?

All very interesting- I don’t know the answers but I think we can in part assess art based on how well it achieves its function. In many ways I prefer a “good” Barry Manilow- (I’d imagine, I don’t know!) professional, slick, a good nights out- concert to a bad opera- (boring, badly cast, under rehearsed, trite interpretation). Maybe I’m just not sure art and craft are necessarily different things. I don’t think you can make good art without good craft- but good craftmanship has its own artistry about it.

I thought the Booker prizes went by nation- “must be time someone from [insert country] won. Who have got from that country? They’ll do.”

I agree that the important thing here is the emotion, the chemistry that is created between the work of art and the person experiencing whatever that work might be. I’ve just come from contributing to a conversation about a book that was judged to be a ‘good’ enough work of art to be awarded a major literary prize, a book I’ve only found one person who enjoyed. I would like to be able to say that this means that this is not a good book, especially as I don’t resepct the views of the person who enjoyed it, but isn’t all that really means is that it didn’t work for me and my friends who probably all have similar tastes to me? I have problems too with this concept of ‘difficult’. Doesn’t difficulty often diminsh with experience? The more familiar I become with something the less difficult I’m likely to find it. ‘Difficult’ therefore also becomes a subjective concept. I find ‘The Simpsons’ difficult, but this is almost certainly because it is a format I’m not used to and therefore have difficulty ‘reading’ as it was intended.

Carl – delighted to have you in agreement! Cam – well, I was really teasing David there rather than equating the two, because no, beauty and art are not synonymous in my book. You’re quite right that they are for some people, and perhaps more so those who need to define exactly what art is (Carey’s first chapter is on that issue!). Talking of art ‘jarring’, when people used to discuss what made literature ‘literary’, one of the suggestions was its capacity to ‘defamiliarise’ or to make even the most everyday seem odd and strange and different. I think that’s just what you are getting at. Archie – Frank Zappa had the niftiest line in quotations. I agree that literature at its best is often disconcerting, but as to its pushiness, well, I really couldn’t comment! Loved both of those quotes about the Booker, and from Calvin! Dorothy, what a good point you raise. You only have to look at someone like Shakespeare to see how even great artists have travelled back and forth across those categories during history. Shakespeare’s been celebrated and dismissed more times than I’ve had literary conversations! Ms Make Tea, the point you raise about craft is a very interesting one. One of the things I was reading said that art originated in craft – tribal tattoos, weaponry, jewellery and so on, and that the purpose of art, descended from those ancient times was ‘to make special’. V. interesting that you should bring that up. Ann – I often think that some art is like very very expensive wine – pretty awful to the palate of anyone but the most experienced, thrill-seeking connoisseur. In art as in wine, you should consume what brings you pleasure, and never need to apologise for that. I also agree with you on the issue of difficulty. I felt exactly the same about the Simpsons, until extended, lengthy, daily viewing of it got me into the mindset…..

Ok, wordpress has ‘done an Archie’ on me, and keeps repressing my comments as spam! Apologies to anyone experiencing the same difficulties, and to wordpress friends who will be without my input until I can get this fixed…

I wonder if you (and/or Archie) have been experimenting with coComment. I used it successfully for a while, then reinstalled it recently after replacing my PC, and have had nothing but trouble commenting ever since. I tried three times this afternoon to comment on your “Advice, Please” post. Each time coComment hung me up. Now that I’ve logged-off the function, the hangup is gone.

Litlove, OH NO! It is the most frustrating feeling! I hope you get back faster than I did. For a while I was feeling very non-personish.

David, Nope – I know nothing about coComment. (oops – I owe you an email)

I daresay I shall have to retrieve this from the spam! It’s a good thought, David, but no, I haven’t been using it. Thank you for the suggestion, however – and Archie, isn’t it annoying! I’ll let you know how I get on.

Litlove,

Thanks for this thoughtful and clever post and the link in your blogroll.

Jan

Jan – you are very welcome! I’ve been meaning to put you on my blogroll for weeks but I haven’t done the big tidy-up yet that I keep intending!

excellent review (over from http://www.thingsmeanalot.com/2011/02/what-good-are-arts-by-john-carey.html)

I haven’t read this book but from the other reviewer’s excerpts my main concern was his weak argument over sacredness. I felt that if he used a different word his argument wouldn’t have held together as well. And that in not acknowledging the otherness that an artist or appreciator feels, because he only views it as ‘sacred’ and therefore elitist and anti-human, he is missing a vital aspect of the art debate.