It’s curious the way that some of the most amusing and comforting writers develop their voice out of personal tragedy. Any reader might be forgiven for thinking that Angela Thirkell led the same sort of easy, untroubled life of the gentry – with visits from the vicar, summer fêtes up at the village’s manor house and children mostly packed off to boarding schools – that the protagonists of her novels enjoy. Her early connections were unusually good: one of her grandfathers was Edward Burne-Jones and she could count among her cousins Rudyard Kipling and Stanley Baldwin. But by the time she began to write, she was no stranger to hard circumstances. Her first marriage was to a singer, James Campbell McInnes, who turned out to be a violent drunk. She had two sons with him, and a daughter who did not survive, before divorcing him in 1917 in a blaze of undesirable publicity. She married again, this time an Australian engineer and army officer, the splendidly named George Lancelot Allnut Thirkell. They went to live in Melbourne, where she had a third son, but the lower middle class life style she had to adopt was not at all congenial to Angela. Claiming it was nothing more than a holiday, she packed up the sons that would come with her and sailed again for England, never to return. And never to marry again: ‘It is very peaceful with no husbands,’ she was quoted as declaring.

It’s curious the way that some of the most amusing and comforting writers develop their voice out of personal tragedy. Any reader might be forgiven for thinking that Angela Thirkell led the same sort of easy, untroubled life of the gentry – with visits from the vicar, summer fêtes up at the village’s manor house and children mostly packed off to boarding schools – that the protagonists of her novels enjoy. Her early connections were unusually good: one of her grandfathers was Edward Burne-Jones and she could count among her cousins Rudyard Kipling and Stanley Baldwin. But by the time she began to write, she was no stranger to hard circumstances. Her first marriage was to a singer, James Campbell McInnes, who turned out to be a violent drunk. She had two sons with him, and a daughter who did not survive, before divorcing him in 1917 in a blaze of undesirable publicity. She married again, this time an Australian engineer and army officer, the splendidly named George Lancelot Allnut Thirkell. They went to live in Melbourne, where she had a third son, but the lower middle class life style she had to adopt was not at all congenial to Angela. Claiming it was nothing more than a holiday, she packed up the sons that would come with her and sailed again for England, never to return. And never to marry again: ‘It is very peaceful with no husbands,’ she was quoted as declaring.

Forced to generate some income of her own, she turned to writing, and published her first novel at the age of 43. She soon found she could publish a novel a year and had almost forty to her name before she died.

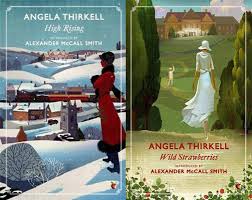

Last summer I read Wild Strawberries, and just this morning I finished High Rising, the first two reissues by Virago. They belong in the same stable as Dodie Smith, and E. F. Benson, as the gentlest form of social satire. She has been compared to Barbara Pym, but Pym had a great deal more to say, of a sharply insightful nature, about loneliness. Angela Thirkell is just there to guide her characters through the mildest storms in village tea cups, before the inevitable and charming happy ending, easily effected when marriage proposals fall so readily from the lips of her male protagonists. In High Rising, single mother and author of ‘good bad books’, Laura Morland (Thirkell in semi-disguise) is drawn into a web of complications surrounding the new secretary of her dear friend, George Knox. The secretary, Una Grey, is a scheming sort with an unbalanced temper and a tendency to send poison pen notes, who is longing to marry some unsuspecting meal ticket. Laura and her saintly friend, Anne Todd, step in to prevent George from a typical Thirkellian fate of marrying in a deep state of inattention – a sort of unconscious coupling that must set up a precedent for Gwyneth Paltrow’s latest conscious uncoupling, perhaps.

None of this plot particularly matters. Angela Thirkell sets out to amuse, with Laura’s state of mind legible in the state of her hair – one particularly taxing morning leaves her looking ‘like Medusa on a heavy washing-day’ and her relationship to her small son Tony, a mix of adoration and irritation, offering wonderful scenes at his boarding school, notably a boxing match where ‘shrimp-like figures’ approach each other with ‘downward clawing motions’ from arms that looked ‘about as strong as boiled macaroni’ before the gong sounds and they ‘fled back to their corners, where they tasted real glory, lolling majestically, arms outspread on the ropes and feet dangling well off the ground.’ In fact, the less that happens, the better Angela Thirkell is at describing it. The essence of her world is a kind of Edwardian nursery, where silliness occurs because of short tempers and wounded pride, but there is always someone sensible on hand to restore order. As in the case of George Knox’s lonely approach to his house ‘which occasionally caused one of Mr Knok’s maids to have hysterics and give notice. But being local girls, their mothers usually made them take it back.’

Servants are intriguing in Thirkell’s novels. While their masters and betters restrain themselves at all times to the most tepid expression of emotions, the mildest of manners and the most distantly tender of relations (or as Hermione Lee phrases it: ‘these light, witty, easygoing books turn out to be horrifying studies in English repression’) the servants are there to tell it like it really is, with strong language, violent emotions and cherished paranoia. They may argue and shout, act compulsively and capriciously, but their emotional stamina lasts well beyond that of their employers. The most disturbing parts of Thirkell’s books are the out-of-date attitudes towards foreigners and the lower-classes, but if her main protagonists patronise their servants, it’s nothing in comparison to the contemptuous patronage they are forced to suffer in return.

It’s a particular and distinct world that Angela Thirkell writes about, one in which small boys want nothing more than to accompany their elders on a hunt, one where kindly doctors don’t charge fees to their favourite patients, where people are generally good and kind and helpful to one another and things work out just fine, thanks to the benevolent intervention of fate. And for the most part, Thirkell’s humour is exceptionally tender, born of loving amusement. It’s a strange, lost world, but a gentle one.

We have to feel for her, then, that one of her sons, Colin McInnes, was a bohemian bisexual who grew up to write books about everything his mother could not bear: ‘urban squalor, racial issues, bisexuality, drugs, anarchy and decadence. He found her novels ‘totally revolting’, a ‘sterile, life-denying vision of our land’.* Unsurprisingly the two of them hated one another, and she cut him out of her will (though she never said anything unpleasant about his books). When we read a Thirkell novel, we get to blindside the uncomfortable, challenging elements of life – that’s the entire point of reading them, to take time out of reality. You do wonder what it must have been like for Thirkell to live there in her imagination all the time.

* Hermione Lee wrote a very entertaining and perceptive essay entitled ‘Good Show: The Life and Works of Angela Thirkell’, which appears in her book Body Parts: Essays on Life Writing. The quote comes from this essay.

How sad that her son was so critical of her work! That must have been extremely sad for Thirkell — surely they could have agreed that there was room in the world for both sorts of book?

You’d think. 😦 It is really sad, because when you read Thirkell’s books with children in them – sons in particular – there’s the most enormous amount of mother love. I guess sons often feel the need to distinguish themselves quite strongly from their mothers and their opinions, and this time it must have got out of hand.

Wonderful post – I have yet to enter Thirkell-world but it’s calling from Mount TBR and I think it will be complete escapism. I was quite stunned when I found out MacInnes was her son, as I’ve read his books and they’re about as far apart in subject matter as you can get. But a shame they couldn’t accept their differences – I guess it’s easier for us with the perspective of time, as both periods they were writing in are now history!

That’s a really good point – they ARE both historical periods now, been and gone. It never hurts to think hard about how nothing lasts forever, and so it’s worth picking your battles. I think you’ll enjoy Thirkell when you pick her up – escapism is the definitive word for her!

What a lovely piece, you capture her world perfectly. I have read three Angela Thirkell books, High Rising, Wild Strawberries and Christmas at High Rising. I loved them and am looking forward to reading more very soon.

They are very charming. I haven’t read the Christmas one, but I can imagine! I’m so pleased Virago is doing this reissue.

Fascinating, I had no idea that Colin MacInnes was her son! I read “Love Among The Ruins” the 17th book in her Barsetshire Chronicles and found it “gentle”. Nothing really happens that is really critical to the characters lives. She also has a vast cast of characters all related to each other and I had a heck of a time trying to remember who was who. I wouldn’t necessarily rush to read another of her novels but it had it’s charms so I’d certainly give her another go one day.

‘Gentle’ is exactly the word! And you nail it, too, when you say nothing much happens that matters. I wouldn’t want to read Thirkell all the time, but when you need soothing books to read, she is reliably escapist. It is odd to think that she’s related to Colin McInnes. I certainly blinked when I found that out!

Fascinating, especially the part about mother and son. I like old fashioned worlds, but am wary about the temptation to live too much in hankering for a safer and more secure past – which I have a weakness for.

I don’t think you’re alone in that! Angela Thirkell absolutely does give the reader nostalgia for a lost golden age, but then there are always a few bits in the novels that make you realise that modern times are better in places. The little boy taking his prize fox tail to bed that he’d been blooded by was a double take moment for me! Mind you, I wouldn’t say no to a housekeeper, if one turned up on my doorstep. 🙂

Thanks for introducing me to Angela Thirkell. As the ripples of Downton Abbey now that it’s 4th Season has finished, I’ve been looking for authors around that period (bet. WWI and II). So glad I now have discovered one more. I must put Thirkell on my TBR list. I love the book covers you’ve shown here too, not that I’m judging the books by their covers. 🙂

Oh yes, this is perfect post-Downton material! And never fear, I find those covers extremely appealling too…. 🙂 Would love to know what you make of her books, Arti.

I’ve tried and failed with Angela Thirkell who was recommended to me for her Barsetshire novels because I had enjoyed Trollope’s so much. I just couldn’t get on with them, sadly. Fancy her being the mother of MacInnes, who does sound a nasty piece of work. But cutting your child out of your will — well, it’s sad, anyway.

You know, I saw that somewhere, the idea that if you like Trollope, you’d like Thirkell. Nope, absolutely not – they are not a bit like each other. Thirkell is a marshmallow writer without the least interest in political concerns. As documents of social history they have their interest, though. But yes, it is awfully sad about her son. I think it’s easier for family disputes to become entrenched than is comfortable to think, though.

Pingback: Sonntagsleserin KW #13 – 2014 | buchpost

Having loved MacInnes’ novels, I must read Thirkell (one day).I bought myself a set of 3 from the Book People including the 2 above.

Oh yes! I remember now. She is perfect for when you have a cold and the world is a cruel place. Very good escapist reading.

Like Harriet I was recommended Thirkell’s Barsetshire novel’s because of my love of Trollope, but although I bought the first one it hasn’t yet made its way from the shelf to the hand. I’m fairly certain that I also have the Hermione Lee book sitting on a shelf somewhere so I think I’ll read the essay first and then see how I get on with Thirkell herself.

You’ll like Hermione Lee’s book – I’d put a nice bet on that one! Thirkell is an author I think you have to be in the mood for. If you want something very soothing and gentle, in the same sort of category as the Mapp and Lucia books, or D. E. Stevenson’s Miss Buncle trilogy, then she is just right. But if you were in the mood for cutting edge, or indeed edge of any kind, you’d save her for another day.

I will definitely keep Thirkell in mind next time I find myself needing a comforting book that is all sunshine and roses with only a few passing clouds to add some spice to the scene.

This was a lovely review of an author I’ve been hearing about thanks to Geranium Cat, who has been reading her steadily for the past year or so. Sometimes a novel in which nothing much happens and everything is happily resolved in the end, is what I need when I need an escape from the trials of life. Your review of Angela Thirkell makes me think is the reason why she wrote the books! lol Especially with that sadness with her son, and cutting him out of her will. Yes, I think I will see if I can find some over here. Thanks for this thoughtful review.

Great post! I think I had an inkling about her first husband, but I hadn’t known that about her son. Wow.

I’ve only read one Thirkell, one of the later ones – County Chronicle, I think. I was overwhelmed at first by all the characters (who were all continuing plots from the previous novels which I hadn’t read), but loved her dialogue and her scene-setting. Like you said, she’s wonderful at writing narratives and scenes where nothing much is going on. I do want to take her books up again, this time starting at the beginning.

Glad you pointed out that her out-of-date depictions of foreigners and the lower-class can make one cringe. I pointed this out in my own review of County Chronicle and got the impression that I had offended her fans by saying so, who perhaps thought I was just being “politically correct” when I was actually truly bothered by those passages.