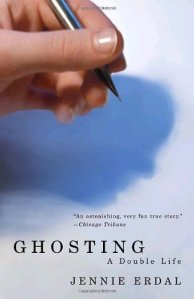

Ghosting by Jennie Erdal is my third creative non-fiction book, and an elegant, flawless meditation on the deep and surprising levels of our relationship to language. For twenty years, Erdal was a ghostwriter for a Lebanese multimillionaire publisher whom she called Tiger. He was a charming, delightful, neurotic control freak, a man of immense generosity and overweaning demands who adored life when it was beautiful and who threatened to sack an employee for forgetting to flush the toilet. On his behalf, Erdal edited huge collections of interviews, two novels, a weekly newspaper column, thousands of letters. It was work that she loved, but which drove her half crazy, although mostly that was due to Tiger’s uncontrollable impatience; on one day when she was nearing submission of their newspaper column, she counted 47 telephone calls from him, checking how she was getting on. Yet for all this hassle, there was no recognition; at publishing parties she was asked if she’d read the book she herself had written. On another occasion,

Ghosting by Jennie Erdal is my third creative non-fiction book, and an elegant, flawless meditation on the deep and surprising levels of our relationship to language. For twenty years, Erdal was a ghostwriter for a Lebanese multimillionaire publisher whom she called Tiger. He was a charming, delightful, neurotic control freak, a man of immense generosity and overweaning demands who adored life when it was beautiful and who threatened to sack an employee for forgetting to flush the toilet. On his behalf, Erdal edited huge collections of interviews, two novels, a weekly newspaper column, thousands of letters. It was work that she loved, but which drove her half crazy, although mostly that was due to Tiger’s uncontrollable impatience; on one day when she was nearing submission of their newspaper column, she counted 47 telephone calls from him, checking how she was getting on. Yet for all this hassle, there was no recognition; at publishing parties she was asked if she’d read the book she herself had written. On another occasion,

I got talking to a magazine editor, a commanding force on London’s literary gossip circuit, who said he had heard that Tiger was helped by “some woman up in Scotland”; adding, surreally, that since no one had ever met her she probably didn’t exist. (…) Concealing your identity can actually be a strange sort of liberation; it can even be self-affirming, since eventually you work out who you really are by living who you are not.’

There was bound to come a time when Jennie Erdal did work out who she was, and when it came, Ghosting was her way of making sense of it all. It’s a book that tries to figure out not just why she became a ghost, but why she stuck with it for so long.

The answer lies to some extent in her dour and respectable upbringing in Fife. Jennie was the kind of child who strained to please her parents, only to find there was no pleasing them. She was sent for elocution lessons from the age of five, with the implicit understanding she would use them to better herself and get out of Scotland. But what Jennie liked were the visits from her uncle Bill, when ‘something happened to the way we spoke.’

The sound of my parents chatting with Uncle Bill was a joy – they used words like scunner and glaekit and puggled and wabbit linked together by lots of dinnaes and winnaes and cannaes. Uncle Bill led the way, and my parents seemed to take their cue from him. In my recollection they seemed happier at these times than at any other, laughing a lot, sharing together, not holding back or being secretive. They still argued with each other, but it wasn’t serious in the way normal arguments were when Uncle Bill wasn’t there. And even when they disagreed, there was still a warm feeling, as if something tight had loosened.’

Jennie grew up to be fascinated by languages, and by the time she was in her late teens had learned Latin, French, German, Spanish and Russian, studying the latter at university. This took her into a career as a translator, about which she had some intriguing things to say:

It’s noticeable that when reviewers praise a literary translation they generally call it “smooth” or “unobtrusive”, often criticising passages that sound “foreign”. It is an odd idea this, judging the translation of a work that started life in another country in another tongue according to its concealment of foreignness… The idea seems to have come about because we tend to assume that a text that doesn’t read naturally in English must be a bad translation. Which isn’t necessarily the case, partly because some literary texts can sound “foreign” in their own language, and partly because a translation into what is generally known as “good English prose” might easily have ignored or lost the integrity of the original work.’

Translation leads her to a meeting with Tiger, and he offers her a wonderful opportunity; the chance to run the Russian list for his publishing house, but to do it from her home in Scotland where she is bringing up three small children. In a few years time, Tiger comes her rescue again after she is summarily abandoned by her husband. He had gone on academic sabbatical to Australia for two months only to come home and tell her he had fallen in love with someone else and wanted a divorce. When Tiger found out about her consequent money problems, he came up with the idea of them doing a book together. He interviewed over 300 celebrity women and sent Erdal the tapes to be edited and compiled. The book was such a success that Tiger decided they should develop ‘their’ brand and branch out into novel writing.

Some of the funniest parts of the book concern the joint novel writing venture. Tiger’s contribution was to tell her ‘everything’ about how the book should go:

Let me tell you the idea. It is very simple. There is a man… he is like me somewhat… he is married… he falls in love with a woman… there is a huge passion… and then… well, we will see what happens after that, isn’t it?’

So Erdal is left having to concoct a whole novel from the thinnest of outlines, and one that mimics the voice of a man, whose real life counterpart is her exacting, finicky boss. Worse still, the only thing Tiger is really interested in seeing in the novel is the sort of graphic sex scene that appeals to him, and which respectable, Scottish Jennie Erdal is horrified to have to write. By the time this first novel is published and Tiger has decided they should write another, Erdal is finding herself blindsided by the dishonesty and frustration of it all.

Outwardly I remained calm and got on with the work in hand, while inside I was building up a quiet fury at every new demand, every fresh enthusiasm. Psychologists call this emotional dissonance, pretending to feel one thing when you experience another – and it is bad for you, so they say. If you hide your negative emotions while displaying positive emotions, you can end up a bit of a wreck. This is one of the reasons why people who work in customer service centres suffer from early burnout – they have to be nice to people who scream and shout at them, and after only a short time they can’t take it any more and start biting the carpet.’

I’ve quoted heavily in this review, for if any book needed to be heard in its own voice, it’s Ghosting. It’s a beautifully written, amusing and entrancing piece of non-fiction, and at its best it asks searching questions about what language does for us, without our being full aware of it, why it matters so who speaks for us, and for whom we speak. We live in language, in it and through it. Language begins as a way of pleasing others, but if we don’t use it to express ourselves honestly, then severe and unexpected difficulties arise. Owning our voices turns out to be existentially far more important than we could ever imagine.

Reblogged this on ENGLISH LANGUAGE REVIEW .

Thank you!

Fascinating. I can’t imagine doing it myself, at any price. Recently at a literary event I was introduced to the best-selling author no-one has ever heard of – Katie Price(Jordan)’s ghostwriter. Currently at work on Katie’s 5th autobiography (at age 35) and with a dozen novels behind her, which have sold untold millions. Apparently Katie’s input into the novels doesn’t extend much beyond choosing a dress for the launch party. It’s a strange world.

Neil, that is an outrageously cool publishing party story! Funnily enough I was in Tescos yesterday and noticed yet another Katie Price novel. I wondered then who the ghostwriter was, as I was pretty sure Ms Price couldn’t put two sentences together. You confirm my unkind suspicions…. 😉

This sounds fascinating, Litlove. I’ll be adding it to my wishlist.

Karen, I’d love to know what you think of it if you read it. It’s a very unusual and intriguing book.

I was hoping that you were going to end this by saying that she eventually told Tiger precisely what he could do with himself, but I suppose he had saved her at some very difficult moments in her life. Is it ever possible to work out who he is?

Well, I didn’t want to leave any spoilers in the main post, but let’s just say you wouldn’t be disappointed. I also think I’m not breaking any rules by saying the publisher in question was Naim Attallah of Quartet Books – the newspaper reviews of the book had it all worked out! Apparently he was not happy about her memoir and rushed into print a novel he had written himself to show he was capable of it. That novel was panned. And really it’s a very tender and appreciative portrait of him (he must have been a difficult boss in reality!).

Interesting and so foreign. I would never be able to write for someone else like that. Short pieces, yes, sure but for such a bossy person… I really understand that she had to write about this.

She’s so right about translation. Very often I see, especially translations from the German praised for their smoothness and the smoothness is often exactly what feels so very wrong to me.

That’s so interesting what you say about translation. I loved the passages in this book about it – it’s a fascinating process and one we don’t think about enough. I don’t know how she did it either. She describes the awfulness of trying to come up with the novels really well – I winced for her!

I have to read this–you mentioned it in your email so it was in my mind anyway, but now this convinces me–it’s especially ineresting since when I was married and all the stuff that happened after–I felt like I had lost my own voice, so I think this would be hugely illuminating. Some books really call out to be quoted from–and thanks for sharing those–it’s nice to get a sense of her “voice”. So, Litlove, you really have to stop doing this–I’ve already ordered the three books you and Dark Puss read together and now I am going to have to order this one as well! 😉

I do think you’d like this – it’s such an intelligent book but in an entirely unpretentious way, and beautifully honest about her complex emotions. The meditations on voice were what I loved most about it. If it’s any consolation, I’ve got Alex winging its way to me! 🙂 I couldn’t resist either!

I laughed out loud at the excerpt where he tells her his idea for a story. He sounds like a character from an Elizabeth Peters novel. I love everything you’ve quoted and will have to get this one from the library posthaste.

I thought about you as I was reading this! I do think you’d appreciate all the parts about life in a publishing house, and it was so good about voice and language and writing. I’d love to know what you think of it!

I remember reading about this book when it first came out (Alex – Tiger’s identity was quite quickly revealed; if you look up some of the newspaper reviews you should find it out…) and thought it looked fascinating and then forgot about it. You make it seem even more intriguing, and not simply an exploration of a difficult relationship but also a discussion of language.

‘there is a _huge_ passion’ 🙂

Helen, it was the parts that weren’t directly memoir that I think I loved the most. Jennie Erdal had such interesting things to say about language, voice and translation. It was a soothing book, too, with one of those lovely, mellifluous style that just flows past in a gentle stream of interesting reflections. I really enjoyed it. Her reproduction of her boss’s speech was very amusing!

Oh so interesting. I have not thought much about what it must be like to be a ghostwriter with someone else getting credit for your successes. I always figured they knew the parameters when they enter the agreement. But I suppose it can get really maddening after awhile. So very fascinating!

I was fascinated by this one – yes, another book my mother passed my way! – especially as Naim Attallah was a larger-than-life character in London when I was a journalist. I’m pretty sure Nigella Lawson worked for him for a while, too.

Pingback: Tales from the Reading Room