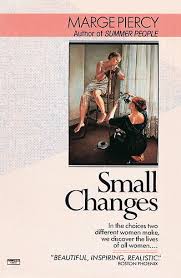

The first book that Dark Puss and I tackled was Marge Piercy’s intense saga from the early 1970s, Small Changes, which we read simultaneously and exchanged comments upon while reading . It plunged us back into the USA on the brink of big social change. From the start this book signals its determined political intent, and musters a fine head of rage towards the spectacle of a culture – a mere 40 years ago – that treated women as second-class citizens, locked in frustrating and thankless roles. The first part focuses on Beth, and opens as she is marrying her high school sweetheart, Jim. Beth is very young and very naïve; she’s getting married because it’s just what women do, and in no time at all, her husband has turned into her jailor. Beth doesn’t like to cook and clean, and she doesn’t want to fall pregnant, all of which infuriates the conservative Jim.

The first book that Dark Puss and I tackled was Marge Piercy’s intense saga from the early 1970s, Small Changes, which we read simultaneously and exchanged comments upon while reading . It plunged us back into the USA on the brink of big social change. From the start this book signals its determined political intent, and musters a fine head of rage towards the spectacle of a culture – a mere 40 years ago – that treated women as second-class citizens, locked in frustrating and thankless roles. The first part focuses on Beth, and opens as she is marrying her high school sweetheart, Jim. Beth is very young and very naïve; she’s getting married because it’s just what women do, and in no time at all, her husband has turned into her jailor. Beth doesn’t like to cook and clean, and she doesn’t want to fall pregnant, all of which infuriates the conservative Jim.

DP: OK, so the writing is much as I’d expect from early Piercy, not too special in itself but clearly she’s building a picture that’s quite plausible and given her early life probably based to some extent on reality. Domestic violence is cleverly handled, with the sexual exploitation of Beth by her husband so neatly expressed when he destroys her contraceptive pills.

L: I was also intrigued to note the way the womenfolk of her family turned against Beth for not behaving in orthodox fashion. The unsubtle message is that women are chattels, possessions in the exchange from father to husband, with no rights and certainly no minds of their own whose greatest use-value is to be found in providing sexual and domestic services. It’s very much a world in thrall to an ideology of domination and submission.

DP: The men are fairly un-redeemed but perhaps that isn’t so unrealistic and this book has a rather black & white approach to male-female relationships. I thought it was interesting that although women are now free to enter into sexual relationships outwith marriage, they are still regarded as subservient in other respects – why on earth they agree to this role of sex plus cooking/washing/mothering is not however clear to me.

I thought this was a good question, and it became one we thought about a lot while reading. Why did women accept a deal that in retrospect looks so poor? Though Piercy’s interest is in depicting a generation of women who can see all the disadvantages and exist on the cusp of rebellion.

In the second part we entered the world of Miriam, an intellectual young Jewish woman whose life improves immensely when she leaves home and undertakes a degree. Her interest is in maths and science and her work is extremely important to her. She falls in love with Phil, a would-be poet and drug addict, and then also with his friend and roommate, Jackson, a man with one bad marriage in his past already. Both men served in Vietnam. They exist in an urban counter-culture and attempt an awkward ménage à trois.

DP: The emotional blackmail used by Miriam’s family is depressingly plausible, though the relationship with her mother seemed a little too stereotypically ‘Jewish Mother’. I shared Miriam’s irritation that her brother is always praised (though he is less academically talented) and is excused the tedious housework just because he is a man. I thought Piercy’s depiction of Miriam’s father Lionel was more subtle; his detachment is a way of coping with a difficult relationship.

I’m interested in the way Miriam is beginning to move away from pure mathematics towards the relatively new area of computing and indeed computational bioscience. I smiled at the mention of the famous DEC 10 which is one of the seminal pieces of computer hardware ever made. It played (in reality) a significant role in places such as MIT so Piercy is spot on in her description here. (Super pictures of it can be seen at this web page ).

L: The thing about the mother-daughter relationships that interests me is the way mothering is akin to moulding; the mothers beg, bully and blackmail their daughters into being/acting the way the mothers feel they should. It’s no wonder that the women grow up co-dependent on others, as their autonomy in the most basic matter of identity has been, if not removed, then severely compromised.

This is the most interesting part of the book for me – the way that nurture is in league with culture. But the results end up in gender rancour. Miriam has never felt loved for who she is, only for behaving the way other people want her to. It’s something she’s fighting against, but the undertow of it is strong. In consequence, love – passionate love – is portrayed as being hard, almost unpleasant to live.

DP: What strikes me is how generically awful the men are! Never helping, always selfish, apparently only motivated by “chasing ass”. On the other side the women seem to be crazily tolerant of some bad/appalling behaviour and extremely nervous of expressing their own opinions – Miriam being the exception.

I believe Piercy is writing a fable here (like Aesop) but I’m sure that sadly much of what happens to Miriam in her attempts to find employment are completely realistic for the time and place. Quite a depressing picture is being painted of the lives of women in and around MIT and Harvard Universities! To be fair it doesn’t look like much fun or reward is being enjoyed by the men in this book either.

In the third section, Beth and Miriam try again to find new ways to live. Beth ran away from her marriage, was found by her husband and dragged back and then finally left him to live in a women’s commune and to find love with another woman (not without its own problems). Whereas Miriam gave up the rat race in the office and married her boss. A man who seemed nice on the surface but who, like Beth’s ex, ties Miriam up tightly in the role of wife and mother.

L: I’m feeling actually upset for the women, who are being cornered ever more viciously. I’d put it down to the way power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. When men had all the authority in marriage and the work place, there was no way of keeping their own behaviour in check.

Any deviation from a role is seen, not simply as a mistake by a woman, but as a slur on their character, a stain, a loss of value. This is particularly true with motherhood, which I’ve always considered to be the part of female reality that feminism forgot.

What’s distressing is that, the first thing women do when free from men is to police one another. All of them are repelled by the different choices of the others and convinced that their own way is best. Not content to live and let live, however, they all try to bend the others to their will and promote their own choices as somehow ‘right’ or ‘better’. The endless power games are wearing.

DP: I’m amazed that Miriam should have, at the tender age of 26, given in to Neil’s demand for immediate pregnancy. She hasn’t even completed her thesis, something which is extremely challenging if you are working and nigh impossible if you have a small child. I’m found that sudden capitulation unconvincing in this story (but probably not so uncommon in reality in this era). Everyone seems to want to control everyone else and it is almost as if there is a “dressing up box” with cultural roles in it, rather than individual identities, that everyone has had to dip into. After you make your choice you are spoiling the game if you don’t like it or conform to it.

L: Heh, well, I found Miriam’s decision all too plausible. I was a month into my PhD when I gave birth to my son. How could I let this happen, you may ask? Easy! I had no idea what I was letting myself in for. It’s interesting; a couple of times you’ve said you found some pattern of behaviour hard to believe, whilst I have found it all too easy. Women’s lives, as far as I can see, and I do hope that’s changing now; I think my son’s generation really IS different – are very susceptible to being enclosed in ‘narratives’ that are very potent.

DP: I finished the book this morning and theme of “I go out to work, you don’t do anything” comes across very loudly from the dreadful Neil. How can he be so controlling? Miriam is trapped by having two very young children and has lost her confidence. I think that is very believable and Neil does nothing to help. He is clever in not becoming visibly angry when criticisng her as this undermines her ability to fight back. Of all the characters in the book I disliked him most even though there is nothing essentially bad about him.

None of our other books provoked quite this much comment! We both agreed by the end that it had been a hard read – long and involved and depressing in places. But the fact that Dark Puss found Piercy’s depiction of the fledgling computer business to be accurate made me feel it was stencilled from life in all ways, even if she had chosen some of the worst gender rancour to portray. We agreed it was a politically significant novel, and I’d love to see this sort of thing read by more young people. It’s worth remembering how things used to be, in the not-so-distant past.

I found your discussion absolutely fascinating. I’m really looking forward to the rest of the week!

You talked quite a bit about the gender roles and made that very interesting point about women buying into them. (I am also looking anxiously at myself after reading: ‘the mothers beg, bully and blackmail their daughters into being/acting the way the mothers feel they should. It’s no wonder that the women grow up co-dependent on others, as their autonomy in the most basic matter of identity has been, if not removed, then severely compromised’ – I have a daughter!) I know Dark Puss mentioned that the writing was nothing special but I wondered if you discussed this at all and whether you had different reactions to it (I’ve never read any of Marge Piercy’s work so have no idea what it’s like).

Dear Helen

I think we agreed on the prose style; don’t look to this book for something really special in the writing itself, look for something important in what is written about. I’m really fond of Marge Piercy’s poetry, perhaps you might start there? Thank you very much for commenting, we really appreciate it.

You don’t need to worry, dear Helen! I cannot in a million years imagine you behaving the way these mothers did. The pressure they put on their daughters was pretty intense and completely bypassed the feelings of the young women concerned. It felt like another country to me. As for the writing, Dark Puss is right – it’s a very, very competently written book. Dense and descriptive so people and situations spring out at you, but she’s not the sort of writer to leave you with artfully constructed sentences. I’d read her again, though. What she had to say was most interesting.

Fascinating discussion of a book I feel no desire whatsoever to read. At the time it was first published I was a young mother, but never participated in the kind of anger and sense of oppression that characterised feminism at the time. I used to puzzle a bit over this — of course my own life was extremely happy and I was lucky to have a partner who had no desire to control me, as these men seem to have done. But I also concluded that a lot of it was owing to the fact that my mother had a fulfilling creative job, as did my aunt, so I saw nothing odd or abnormal about women going out to work. I think this partly addresses DP’s question about why women allowed men to treat them in this way (sex plus cooking/washing/mothering) — it must have a lot to do with the fact that their mothers did it before them and so they didn’t question it.

Looking forward to the next installment! Thanks.

Hi Harriet, I think your hunch is a good one!

Harriet, I think you were really fortunate. I was discussing this era in the bookshop this morning, and my manager was recalling a film she’d recently seen about Barbara Castle and the battle for equal pay through the unions. That was the early 70s when there were so few jobs for women and most of them shockingly paid. To avoid that sort of situation must have been a clever move on the part of your mother and aunt.

This was a fascinating exchange and thank you for sharing it! What a wonderful idea you both had and carried through. Even though I lived through that era, I was a kid with a kid’s perspective. My eyes were opened by one of Alice Munro’s late short stories where she explained how the dynamic occurred. IE Married young men went out; married young women went in. Suddenly there was a huge divide of experience and expectation: men to be competent and in command; women to remain teenagers and without any input from the larger world. I don’t know if I’m explaining this well. She put it so beautifully that it created a vivid picture.

Dear Lilian, the idea was all Victoria’s, though the conversation that led to it was (I think) sparked by me. We both feel it has been an excellent collaboration and I have certainly learn’t much from the experience.

But I have not learned to spell properly yet …

Lilian, if you remember which short story it was, do let me know. I want to read more Alice Munroe – the only book I’ve read by her so far I thought was excellent. I was only a child, too, in the 70s and it was funny revisiting this era. I could feel it in places, but not recall it.

I don’t remember the name of it, but it was in Dear Life. You must read it! It is one of her best and it is her last. She said at 81 she is retiring from writing. She said that before and didn’t, but I think she means it. And it’s wonderful.

I just read Piercy’s Vida, thinking you were discussing it. It has been a while since I read BL, but I loved it and thought its depiction of gender roles in the 70s was very very realistic. There were exceptions, but this was the agreed upon norm. In some ways your comments on BL work for Vida as well; early Percy, women fighting each other, and irredeemable men making demands on “their” women. Vida centers on individuals active in the radical wing of “The Movement,” and makes the point that even men who claimed to be working for justice and fairness for all behaved tyrannically toward “their” women. Vida’s sister movies into women’s issues, but Vida herself agrees with the men that rape was too minor an issue to worry about until “After the Revolution.”

DP’s idea that MP was exaggerating was interesting, and I think a sign of how gender affects how we read. The men in MP’s books, and in real life at the time, would never have seen themselves as doing anything wrong. Some men are still in that place, but at least there is public condemnation of such behavior.

I agree with DP that sensitive men can and should read “women’s books” to expand their understanding of other human beings. In Vida I had a real sense that MP was writing for the men in The Movement as well as the women; telling them to clean up their act.

As to why women accepted that treatment… There were few jobs open for women to support themselves and their children. After WWII, the women who were the mothers of MP’s women, and of MP herself, were just glad to have men back home alive. And excellent book as to why that generation of women rebelled is Young, White, and Miserable: Growing Up Female in the Fifties.

Hello mdbrady and thank you very much for your comments. In what way did I imply Piercy was exaggerating? Now as to your comment about “women’s books”, I’m not at all sure I’ve used that term. This is a book written by a woman and predominantly focussing on the female characters, but I don’t read it as a book aimed at or mainly for women. At least that’s my thesis; we will see how well (or how badly) it stands up to this week’s discussions over this and the other two books!

Sorry. I overstated. I was referring to your comment about some situations, such as women’s submissiveness, being “amazing” while litlov recognized them as commonplace. I am less sure than you that MP wrote primarily “for women,” though ES probably does. In Vida, MP was certainly calling the men to account.

I am glad you two are doing this and calling attention to how accessible “women’s books” are to men willing to attend to them. I think novels are one of the best ways for any of us to understand those we tend to see as Other in our lives.

What an interesting comment! I wanted to put in the post (but didn’t have space) a quotation I’d recently come across from a biography, in which the author spoke out against ‘generational chauvinism’. or the tendency to look back at the past with scorn and lack of forgiveness for its illiberal idiocies. He said it was simply because it was so hard to think oneself back to past as it was. And I thought, yes, the difficulty we have in understanding why things were the way they were is a perfect mirror of our ancestor’s inability to imagine a different future. There were reasons why gender relations were stuck in their rigid roles, and for the people who lived them, those roles were natural, inevitable, normal. I will have to look up that book you mention.

I must also say that I felt I tested Dark Puss very thoroughly in our reading challenge and he accepted and read and, in some cases, enjoyed a really impressive range of reading I would have classified as basically woman-oriented. It was interesting that our responses – though they were different in places – were often fundamentally similar. I actually found this really heartening!

Nice example of why we need historians to help us see that other generations had reasons for behavior we reject for ourselves.

I expect that you two will agree most of the time. When you disagree or see things differently, it may or may not be gender-related. After all, we do live in gendered societies and have been trained to see life from those perspectives. I, too, and heartened by men like DP who read and listen to what women are saying. As I am by male writers who write sensitively about women. Those readers and writers are the best hope we have.

I got married 41 years ago,straight out of college, so it would seem I should recognize domestic oppression. However, like drharrietd, I never felt (or was) oppressed. Like most stereotypes, the ones about modern mid-century men are largely untrue – at least from my experience. Now, it is true that it was more difficult for a woman to excel in the professions, but it still wasn’t impossible. My marriage eventually did come to an end, but for reasons that had nothing to do with power struggles. Sandwiched in between the beginning and the end were days and years of mutual respect, shared child rearing, and other really good stuff. I was also the beneficiary of a husband who loved being in the kitchen and was seldom happier than when he was making a gourmet meal. (Gosh…I miss the marinated grilled tuna with fried rice). Personally, I think the myth of domineering husbands (although I’m sure there were many out there) lives more in the imagination than it did in real life. But, our perceptions are always governed by our personal experiences. Anyway, it sounds like a pretty depressing book, but I enjoyed hearing your discussion of it.

First of all, I am so happy to know that your own experience was a good one, and not troubled by the uglier side of relationships that we were reading about. Good! I’m amazed that you were aware of women excelling in their professions as certainly in the UK in the 70s, there was definitely a glass ceiling in place and it was still normal for women to give up work when their children were small, unless they absolutely had to have the money. Perhaps America was always more advanced in that way.

I guess for me, the point with the gender relations that Piercy is making is that, where controlling male behaviour existed in marriages, it was taken as perfectly acceptable. Normal, even. The fact that it could and did happen – and prior to the mid-1970s even in America, marital rape was not a crime (it was first criminalized in South Dakota in 1975, and the last state to criminalize it was North Carolina in 1993; thought you might like the legal detail!) was something that needed attention brought to it. I definitely felt Piercy was shining some cold, hard light on social circumstances that needed to change. Even if there were exceptions, the vulnerable needed to be protected as a general rule. It was a depressing book in places, but it did show us how far we have come – far enough, I think, to forget how things could be, and it’s good to be reminded.

Not sure what you mean by “I’m amazed that you were aware of women excelling in their professions as certainly in the UK in the 70s, there was definitely a glass ceiling in place and it was still normal for women to give up work when their children were small, unless they absolutely had to have the money.” My point was it was more difficult in the ’70s for women to break into the professions than it is today. But today, most law school grads in the U.S. are women. Hurrah for us, I guess. I know nothing about the U.K. and I don’t think of self-worth or accomplishment in terms of gender, and I would not enjoy an author who does. That was really all I was saying. The longer I live, the more I realize how little I know. My experience is not the experience of every woman, but I can hope that people, whatever gender, can strive to become their best self successfully.

Oh I’m sorry, I misread you! I thought you were still talking about the time scale of the book, rather than the present day. And yes, hooray, in the present things are vastly improved. I was simply comparing the UK to an America that I thought must have been very advanced, duh!

No, the US was not doing better in the 1970s. I’d say worse on gender issues–maybe because I know little about other places. Your point about what was considered normal is a good one. Yes, there were exceptions, but why was it an “exception” for wives to be treated well in the 1970s? Yes, norms are changing, and better jobs available for women, but not universally.

That’s okay, Litlove, I don’t understand what I’m saying myself half the time!

What a fascinating post and so interesting to see two different perspectives of the same book, and one that was/is a ‘consciousness-raising’ sort of story. I was wondering whether it would come off as being a stereotype or cliché rather than a believable reflection of women’s and men’s lives at the time, but as it was published in the 70s, Piercy was experiencing the things she was writing about first hand. Thankfully much has changed since she wrote this book, but to be honest I still see in some of my friends’ marriages the sort of gender delineation that was so common before–women dealing with all the household chores, most of the child rearing while the men work outside the home (and sometimes the women do, too, and still do all the work inside the home)–though it it less with friends who have grown up here in the US than friends I have who are immigrants. I have read MP’s Gone to Soldiers at least three times–next time I will have to read it in light of the sorts of issues you raise here. Thanks so much for sharing your conversation–and I am looking forward to your next discussion (hopefully you’ll be talking about the other books you read?).

Hello Danielle, next book is up today and the third book on Friday. Thank you very much for your comment.

Danielle, I read this fascinating book a couple of years ago about working mothers, particularly in the classic professions – law, medicine, academia and commerce – and it included a survey showing that working women mostly did the housework and childcare on top of their day. The average number of hours a week they put in was 100. That was my experience too, and it finished me off! So I think that having it all has meant, for a lot of women, doing it all. And that book was talking about women in well-paid jobs – I shudder to think what immigrant women have to do to get by. The Marge Piercy was really good and avoided stereotype by giving the reader just so much information about the characters and such detailed and intense involvement in their lives. I’d definitely read her again.

I recently read my first Marge Piercy book (Woman on the Edge of Time) though I think that one is possibly less black-and-white on the women and men issue. It sounds like a thought-provoking book but perhaps too upsetting-especially as I’m sure I’d relate overmuch to the character that shares my name!

Please don’t be put off. This book is very well worth reading.

I’ve got Marge Piercy’s Gone to Soldiers and her memoir Sleeping with Cats, so I was interested in your thoughts on this one. It was interesting to follow your conversation. I feel I’d be infuriated reading this which, in a way, is not a bad sign.

I found DP’s comment that it read like a fable interesting. Sometimes it’s important to exaggerate to make the message heard but I’m afraid a lot was really taken from experience.

Hello Caroline, you will be more than infuriated you will be speechless with anger at some points! I do not know of a book that has made me so upset at the casual “enslaving” of women by (primarily) thoughtless men that seemed to be built in to the world these women found themselves in. Even more upsetting in some ways was how often it was accepted as something that really couldn’t in the end be changed. Perhaps Miriam’s story was the most bleak in the way she was treated by Neil. Do read it!

I love Piercy and had a go at a number of her novels in the 90s. I missed this one though! How could I have missed it? Love the discussion. It is a curious thing how mothers and female peers push women into conforming. It is so very sad and I think, reveals just how oppressed women have been for so very long, and in some ways, still are.