The Notebook of Malte Laurids Brigge is the extraordinary journal of a Danish nobleman stranded in a surreal pre-First World War Paris. Ostensibly this is a novel, but the narrator’s sense of extreme alienation in a big foreign city, and his endless questing for the right kind of apprenticeship in art are direct transpositions of Rilke’s experience. ‘Novel’ also seems an uneasy word to use when the narrative alters as it progresses, moving from the recognizable form of a journal written by a disoriented immigrant, to an autobiographical retelling of some intense experiences of his childhood, to a strange yet wonderful compilation of legendary tales. This curious journey through the realms of storytelling comes about because Malte, the narrative alter ego, is poorly equipped to handle severe culture shock. His reaction to the disorientation of Paris, with its streets full of sick, poor people, and hideous, shrieking trams, is to experience himself as hopelessly porous, undefended against the raucous modern world, and menacingly invaded by it.

The Notebook of Malte Laurids Brigge is the extraordinary journal of a Danish nobleman stranded in a surreal pre-First World War Paris. Ostensibly this is a novel, but the narrator’s sense of extreme alienation in a big foreign city, and his endless questing for the right kind of apprenticeship in art are direct transpositions of Rilke’s experience. ‘Novel’ also seems an uneasy word to use when the narrative alters as it progresses, moving from the recognizable form of a journal written by a disoriented immigrant, to an autobiographical retelling of some intense experiences of his childhood, to a strange yet wonderful compilation of legendary tales. This curious journey through the realms of storytelling comes about because Malte, the narrative alter ego, is poorly equipped to handle severe culture shock. His reaction to the disorientation of Paris, with its streets full of sick, poor people, and hideous, shrieking trams, is to experience himself as hopelessly porous, undefended against the raucous modern world, and menacingly invaded by it.

Culture shock works its strange magic on Malte Laurids Brigge, and what is at stake is no longer simply his own alienation, but the way that the great, unwieldy concept of Life is seen and understood. As for so many writers of this period, the epic changes that took place at the start of the twentieth century seemed to put in doubt the individual’s capacity for self-knowledge. A complete overhaul of representation was needed, for, after all, how are we to know ourselves except via the stories we recount? Nowhere was this more apparent than in the new phenomenon of city life. The concept of being an anonymous stranger in a crowd was experienced as exhilarating and destabilizing by any number of authors, poets and painters. Malte’s attempts at writing about this new reality do not go well. Describing the Paris that surrounds him means allowing himself to change so that he is at one with his surroundings, not the freaked out alien citizen he feels himself to be. Malte recognizes that a change in his perception will mean an ineradicable change in his internal configurations, and the prospect of a switchover to Parisian settings appears to him in a terrifying light

So what does Malte Laurids Brigge do, in the struggle to overcome his extreme alienation and find his poetic creativity (knowing as he does, that the two are magically linked)? The first thing Malte does is to trust to his own unfolding, and gradually the composition of the narrative alters. At first Malte writes a great deal about his experiences in Paris, interspersing his journal with memories of his childhood. Those reminiscences begin to take center stage, until his life in the city is completely obscured by the weight of surreal memories from his past. However, this is not Malte’s final literary destination. The problem with his past is that it reflects back to him the roots of his current suffering without offering any resolution. What Malte wants is a narrative form that will allow him to transcend his troubles and still remain himself.

So, once again the focus of the narrative shifts, and what Malte increasingly tells are parables, and allegories, and stories that have an odd, fairy tale slant to them. How can this possibly help him come to terms with himself, one might reasonably wonder? And yet what Rilke suggests is that autobiographical narrative may not be the best way to approach oneself in language, and that we may find ourselves most fully present in what we write, when we are wholeheartedly engaged in writing about something completely different.

For instance, in the last story of the narrative, Malte rewrites the tale of the Prodigal Son. In his version, Malte claims that the significance of the story is to be found in the problem of excessive family love. The son leaves because the weight of adoration and expectation lies too heavily on his shoulders. ‘He could not put it into words, but when he wandered about outside the whole day and did not even want to take the dogs with him, it was because they too loved him; because he could read in their eyes obedience, expectancy, participation and solicitude; because even in their presence he could do nothing without pleasing or giving pain.’ What the Son wants is, sometimes, to be nothing more than a ‘transient moment’, to be endlessly transformed by the beauty of the world around him. The freedom of our birth right (though we give it away so quickly) is to be exactly what we are, not forced into a shape of compliance by others. Discomforted by love, the prodigal son wants to confront the question of who he might really be without the influence of others, or as Malte describes it, ‘The secret of that life of his which never yet had been, spread out before him.’ Who might we be when we are alone? If we were allowed the purity and simplicity of just being ourselves? What, then, if the departure of the prodigal son were not an act of selfishness, but one of integrity, committed by a man who could not continue lying just to meet the desires of others? Could we perhaps see that it is the love of the family that becomes an unnatural and selfish constraint upon the son, who is otherwise asked to abandon his self in order to please?

So the tale of the Prodigal Son becomes, in Malte’s rereading of it, a tale about ways of loving differently, about viewing our obligations to others differently, and about finding authenticity in a kind of open emptiness. Being receptive to the moment, being flexible, not compliant, becomes the guiding insight of the Prodigal Son. Even though this is the Prodigal Son’s story, the analogy with Malta and his writing is evident. For Malte, too, comfort has finally come in retelling old stories, at the risk of their distortion, so that they contain his personal truth, rather than producing any sort of traditional narrative. Malte abandons the stories that concern his own existence, because if he stares too long at his self it becomes an encumbrance, a paralysing act of self-hypnosis that fills him with anxiety. Malte and his Prodigal Son tell us that what lies closest to the heart, what forms the very substance of our soul, can never be approached directly and explained. It can only be spoken of in allegorical form and it can only be viewed indirectly, like the eclipse of the sun. To try to face it full on would leave us dazzled and overwhelmed, and certainly none the wiser.

This has long been one of my favourite books, although it disconcerts the reader over and over again. It makes you question your expectations of stories and what they should do, but it does so with that unmistakable ring of Rilke’s voice, his piercing and passionate sincerity.

ETA: do read Emma’s review also.

I’m sorry I didn’t have the time to read this while you did! It sounds wonderful and I will definitely read it eventually. The retelling of the Prodigal Son takes a definite Emersonian turn. Emerson is all about finding the work you were meant to do and pursuing it no matter what.

I forgot to add that I love your “I am not a serial killer” photo caption!

Oh my! Sounds like I must get a copy of this one. I’ve been meaning to read Rilke for years, and this sounds terrific the way you describe it. Fairy tales? Story telling? Autobiography and journal all tied into one? I’m there! I’d never thought of the Prodigal Son in that way, but it makes very good sense, especially since so much of what Christ was about was challenging biological family ties and tribalism.

Would you recommend this as someone’s introduction to Rilke? Shamefully, I’ve never read anything by him! Every time I intend to give him a go (even just his poems!), I get intimidated and worried about translation issues. I still want to though! Nobody says anything but nice stuff about Rilke.

THANK YOU VERY MUCH FOR YOUR REVIEW-.- HAVE READ OVER AND OVER THIS BOOK AND NEVER HAD I FOUND SOMEONE TO

EXPLAIN IT TO ME NOW I ENJOY IT MORE

I wonder if the last part of your post means that it is not one of your favourites anymore? I also wonder how much it chnanged from one reading to the next. Reading your review makes me realize that it has been very long ago since I read it and what I cling to is my memory of the feeling I had when I read it, a very enchanted feeling it was, and not so much the memory of the book itself. My story of my reading of Malte Laurids Brigge.

Hasn’t Gide written about the Prodigal Son as well? They knew each other.

Interesting. Makes me also think of Les Faux-Monnayeurs, another exploration of story telling.

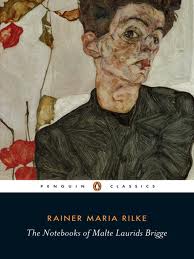

Such a beautiful introduction! Love that Schiele painting on it, it seems so apt for the book.

I’ve never read this but it sounds fascinating.

Great review! But note that the narrator is Danish.

I loved this post, and I’m added the book to my wishlist! 🙂 (Also, the caption you put on Rilke’s photo made me laugh…the camera certainly didn’t love him, lol.)

I had good intentions and even have that same edition of the book but my planning is, as always off. After reading your post, though, I think I’d rather have this as an introduction to it before diving into it–it’s a slender book with lots to think about I see. I do have to ditto Jenny, though. I’ve never read Rilke, so would this be as good a place to start as any?

I haven’t had the chance to read this though I do love Rilke. It is on my list for sure and now that i’m on best rest, it might have a chance of being read.

How interesting to read about Rilke’s exploration of how to write about the self, after thinking so much about the same issue in Lauren’s Slater’s book. I like the idea that autobiography may not be the best way to write about the self, and that we may see and portray ourselves most clearly when focusing on something else. I’m looking forward to getting to this one, and I’m happy it will help me think more about life-writing.

Lovely! I always enjoy your insight so much, litlove. You probaby already have it on your radar, but just in case you don’t, here’s the link to a gorgeous blog: A Year with Rilke.

http://yearwithrilke.blogspot.com/

Stefanie – that’s quite okay! Rilke’s not going anywhere, and it’s always best to read whatever you most want to read at any moment, I think. I had never thought to make the connection to Emerson, how interesting, and thank you for liking my caption! The spirit of frivolity always takes me over when I type them, and often I wonder whether I should stick to being serious!

Emily – Once I’d posted this, I wondered whether I should have said more about the experience of reading this book, which can be a bit bewildering at times. I wrote about how I’d come to understand it, and it makes a more coherent picture than first impressions of the novel itself. But do try it because it is such a beautiful book, so rich that I’ve never found a reader who minded its strangeness.

Jenny – he is just such a lovely writer. This was what I read first, and I still find it easier to get into than his poetry. I love the Duino Elegies, but they can be very disorientating for a first read. I’d go with this, or, at a pinch, his ‘Letters to a Young Poet’ which are all about his philosophy of writing. But only pick those if you are a real letter fan.

Victor – thank you, that’s a lovely compliment.

Caroline – oh no, it’s still one of my favourite books of all time. Funnily , for me, it never seems to change when I read it. Pretty much every book changes over time, but not this one. Although I can completely sympathise with the desire to hang onto an original experience of it. I know very little about Rilke’s life – had a biography out of the library this summer for two months and never managed to get near it! I will have to take it out again.

Nivedita – thank you! The picture is so striking, isn’t it?

Lilian – you have to like the modernists, I think, to really fall in love with this. But I do, and so I did. 🙂

Jim – duly changed! When I first read your comment, I though, but I know he’s Danish…. duh! Why does one’s brain think one thing and type another?

Eva – I’d love to know what you think of it! I think if you like Woolf and Kafka, chances are you’ll like Rilke. And I’m so glad you liked the caption – poor Rilke, I’m sure he was lovely in reality…

Danielle – I think it’s an easier place to begin than his poetry. It’s not that hard to read – every bit as you go along makes sense and is accessible; the tough thing is sorting out the relationship of the different parts to one another. But please don’t worry – read it whenever the time is right! I think it’s doing justice to Rilke to only read him when you feel llike trying something new.

iwriteinbooks – if you like Rilke already, I’m sure you’ll love this. I do hope he proves a good companion for convalescence – he’d love the idea of that, I feel sure.

Dorothy – to be fair, Rilke is a very unself-conscious narrator, no meta dimension for him, questioning what he’s doing. He tends to move through these different phases without a great deal of explanation. But that makes him interesting about life writing in a very unique way! I’d love to know what you make of this. It’s good for readers who like to savour their stories.

Deborah – thank you for that! I had it in mind to seek out that blog, as I have heard of it, but I didn’t know quite where to find it. You’ve done me a very useful service there!

I was looking forward to reading this and I waited to have a quiet moment for it.

Your review gives an amazing taste of the book.

You managed to summarize and explain the part I struggled with (the one about the Prodigal Son and love). I see I had understood the main argument but not the details. I was confused and unable to put it into words. (even in French words)

PS: the French edition also has a Shiele painting on the cover. Not the same one.

Emma – I forgot to link to your post! Let me sort that out right now. I’m so glad you liked the review – Rilke really IS hard to write about – and I cheat in a way because I’ve had such a long time to think about it!

I think you are probably very right and am keeping him on my pile for the right moment! 🙂 Still, thanks for the gentle push to finally at least buy something of his–I know many people love his work!

Thanks for reminding me about this book, litlove. I read part of it when I was much too young, and picked this up as an e-book a little while ago, waiting for a quiet time in which to read it. Rilke really was a very interesting man and, if his letters with Andreas-Salome are any indication (I read a couple years ago), cared deeply about what it was to create art, what it was to live.